A continuation of an abridged series about Riley Technologies’ Bob Riley.

So much did Tommy Kendall’s all-but-catastrophic misfortune overshadow the 1991 Watkins Glen Camel Continental GTP race that few remember Juan (please don’t call me “Manuel”) Fangio II and his No. 99 Dan Gurney All American Racing Eagle Toyota HF-90 scored the team’s first win of the 1991 season.

(NOTE: Starting a roll that would lead to three total wins - two with a brand-new Eagle Mk III - in 1991’s final five races. Fangio and teammate P.J. Jones over the following two seasons would, some insist, change the very face of prototype sportscar racing by winning 70-percent of 1992’s and 91-percent of 1993’s prototype races. In 1992, Fangio, assisted by Kenny Acheson and Andy Wallace at Daytona and Wallace, only, at Sebring, which the pair won, took first place in seven races while P.J. Jones won three. Interestingly, AAR’s stunning win run was interrupted only by its “no-show” at the 1993 Elkhart Lake race.)

“I was sick; just sick,” Bob Riley said, recalling the rush of feelings in the aftermath of Kendall’s Watkins Glen wreck.

“Race car drivers are paid to take risks and every one of them understand they regularly face risks that can negatively impact them and can come unexpectedly, even be caused by someone else.”

“Anyone involved in motorsports, I don’t care where it is – Karting, Grand-Am , open wheel, wherever – understands there are inherent risks in the sport.

“Yet, motorsports, back then and more so today, is safer per-mile traveled than on public roads.

“No one in racing wants to see others get hurt, so we try as hard as we can to minimize the risks, but you just can’t get rid of ‘em.

“Look at history and you’ll see trial and error is the single most-successful method of human discovery. We learn from mistakes more than through any other method.

“Even with today’s CFD (computational fluid dynamics) the bottom line is that humans write the programs that the computers use to figure out what a car might do in a given set of circumstances. Humans – at least insofar as I know – haven’t yet figured out how to figure out everything there is to know.

“Shoot, back then, computer time for anything, much less CFD, wasn’t near as available as it is today – we’ve even got a CFD-dedicated computer here now at Riley Technologies – but even today you just can’t walk over to your nearest supercomputer and use it like you can an ATM, even though today’s everyday computers probably have more computing power than the supercomputers back then. The numbers still just take a really long time to crunch.”

“Even though I’ve always tried my best to make every car as safe as possible - because it’s never fun or easy seeing something like what happened to Tommy – it can happen to anyone,” Riley said.

“Still, interest in the Intrepid pretty well just dried up overnight after his crash,” Riley said.

The Bad At The Glen notwithstanding, by many standards the Intrepid was doing things other cars weren’t and had done so in rather spectacular fashion, to boot.

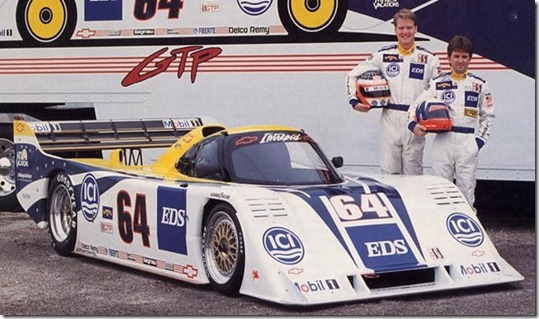

Although Miller Racing was absent in two of the 1991 season’s 14 prototype races and that Kendall started (counting only his No. 65 Intrepid) only but four of Taylor’s 12 races, outside of Taylor’s New Orleans win the team combined to additionally put their two Riley designed Chevrolet-powered RM-1 Intrepids on eight race front rows, of which six were poles (Taylor, 4; Kendall, 2); scored the fastest lap in seven races (Taylor, 5; Kendall 2); and, stepped onto four race podiums (Taylor, 3; Kendall 1).

At the end of 1991 Taylor and his No. 64 Chevrolet Intrepid alone finished with a fourth-place or better in 75 percent of the races in which they competed.

Whether the drivers or the prototypes in which they competed, by 1991’s end the Intrepid RM-1 and its pilots had faced the winning likes of Bob Wollek and Louis “John Winter” Krages in Joest 962C Porsches; Juan Fangio II and Rocky Moran in two models of Dan Gurney’s AAR Eagle Toyotas (that at season’s end had begun a 17-race, multiple-season win run); Davy Jones and Raul Boesel running three distinct TWR Jaguar models; as well as at least three different Nissan prototype chassis driven at different times by Bob Earl, Chip Robinson and Geoff Brabham, the latter capping 1991 with a fourth-consecutive prototype driving championship.

Having recorded three poles, three fastest race laps on his way to five wins, Tom Walkinshaw Racing’s Jones and his XJR rides were the best of the rest insofar as “wins” were concerned but still fell short of winning the season-long championship fight ultimately claimed by Nissan’s Brabham, winner of one 1991 race (Sebring) and “Mr. Consistent” in the remainder.

When measured against the extent of the financial, engineering and manpower depth available to that day’s top factory efforts, Jim Miller, Riley and Gary Pratt’s comparatively underfunded Intrepid design more than held its own.

Yet, despite the car’s clear promise, with 1992 on their mind, Miller Racing would whittle itself from two standout drivers to one – and it’d go with Kendall.

“I’d developed the car, won poles, led laps, won a race and there I was, out of a job,” Taylor said. “I just didn’t understand it.

“That was the beginning of me trying to figure out where I was going to go with my racing career and the manner I’d undertake it.”

Though Taylor would again give the Intrepid another go – with Tom Milner managing a couple of “borrowed” Intrepids that Riley said “were returned in better shape than when Wayne got them” – the Intrepid’s spectacular underdog moment had largely passed.

As prototype racing budgets grew well beyond what privateers could afford – at least those desiring and having a realistic chance at winning – and largely caused “the little guy’s” withdrawal, competition rules changes for 1994 were already in the air and would bring some back, along with again pairing Taylor with Bob and Bill Riley.

Next: the Mk III

Later (and enjoy the weekend),

DC