Part Three of an abridged look at Riley Technologies’ Bob Riley.

MESSRS. MILLER, RILEY AND TAYLOR JOIN

Perhaps hard to imagine today, there was a time when

With Roush Protofab and Ford’s 1980’s domination of Trans-Am and IMSA GTO racing, Bob Riley and “brilliant” were frequently mentioned in the same breath by those of that period’s racing world.

At the same time but with somewhat less frequency, Taylor's name was just emerging from one of racing's faraway but notable corners, South Africa. Yet, it wouldn't be long before "Riley & Taylor" would be just about as synonymous as Proctor & Gamble, Pratt & Miller or Taylor and Burton - that is “Elizabeth and Richard” and, some might say, ending much the same way.

Driving a Ralt RT4 in a come-from-behind points surge that literally concluded the 1986 South African season's last-chance race at Kyalami in Cape Town, Taylor overtook a spinning Bernard Tilanus in the race’s waning lap to win the South African National Racing Championship.

With an eye firmly fixed on building his racing future into international recognition, Taylor in 1987 made a second trip in three years to France's Circuit de la Sarthe, joining fellow South African racing icon George Fouché and Austrian Franz Konrad in a Kremer Porsche 962 for the 1987 24 heures du Mans.

The three drivers would finish fourth overall and, combined with his previous 10th-place overall effort in the '85 Le Mans, Taylor in two attempts had managed to score two top-10s in a race characteristically known to whittle the race’s field with each passing hour.

Gaining the notice of Spice Engineering, it wasn't long before Taylor joined the English-based manufacturer's factory driving corps and, a couple of years later in 1989, was sent to the U.S. so as show the Americans how to really wheel a Spice.

With a SE89P-Pontiac "Firebird" GTP underfoot for that season's final three IMSA races, Taylor closed the stretch run with a pole in the season finalé at the Del Mar Fairgrounds north of San Diego, Calif. - a track he'd not even previously seen.

By besting the time of a second-fast and fellow Spice SE89P-Chevrolet driver Bob Earl, who finished the season 8th in 1989 IMSA GTP points and was on his way to a 1990 Electramotive Nissan ZX-T ride, Taylor's Del Mar qualifying performance caught the eye of Earl's co-driver and team owner, Jim Miller, who sought Taylor after the race.

"Jim Miller's car (Spice) was second to me in Del Mar (qualifying) and after the race he said 'We should talk,'" Taylor recently recalled.

"I told him I was literally on my way back to South Africa, that I'd already shipped all my personal effects back and that I had a plane to catch right after the race and that we'd have to talk another time. So off I went."

"We had no contact whatsoever until he called me in South Africa over Christmastime and said, 'Come race for me.' I landed on U.S. soil on January 20th, 1990," Taylor proudly said, adding the arrival would prove long lived.

Joining Miller Racing (aka, "MTI Racing") for the 1990 season and driving the No. 64 Spice SE89P-Chevrolet that Taylor bested a few months earlier at Del Mar, a lack of preparation time dissuaded the team from attempting that year's Rolex 24.

Paired as co-drivers for the remainder of the 1990 season, Taylor and Miller campaigned a car that often posted top-five qualifying times - Taylor scoring a pole at San Antonio - yet was vexed by a mixture of mechanical woes, accounting for eight of the team's DNFs that season.

When the mechanical ghosts and goblins were absent the Spice and its drivers often performed well, but not good enough to overcome the negatives, leading to 1990 GTP championship points finishes of 13th and 19th, respectively, for Taylor and Miller.

With Spice Engineering on the front-end of a multi-year, downward spiral caused mostly by a fast-changing rules landscape that ultimately led to its demise (but not before combining with Acura and Parker Johnstone to win the 1991, 1992 and 1993 GTP Lights championships), Miller looked to leave his Spice behind and start the 1991 season with a clean slate.

AN INTREPID ENDEAVOR

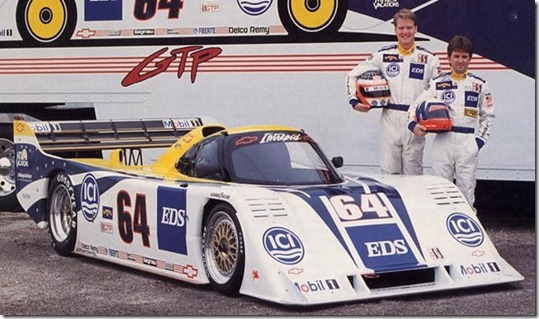

And there you have it, ladies and gentlemen; springing forth from a ubiquitous restaurant napkin was the birth of one of the 20th century's more iconic GTPs, the Intrepid RM-1 (left, with Tommy Kendall and Wayne Taylor, L-R).

"Then we talked about some figures and Jim said if Gary and I would take care of building the car, he'd take care of finding the sponsor," Riley said.

"We'd originally wanted to put a 1,000-horsepower Judd in but Jim walked into the shop one day and said, 'I've got a sponsor and they're funding two cars!'"

"The sponsor Jim brought in was Chevrolet and, of course, Chevrolet wasn't going to have anything but a Chevrolet in a car it sponsored, but by comparison it only made about 800 h.p."

Tommy Kendall, by then under contract to General Motors after piloting a Mazda RX-7 to the 1986, 1987 and 1988 IMSA GTU driving championships, came with the two-car Chevrolet deal.

With Miller again opting from the endurance races, the Rolex 24 serving as the season opener then as it does to this day, and inasmuch as Taylor helped develop and was most familiar with the Intrepid, Taylor wasn’t displaced in favor of Kendall, who got the team's existing Spice SE90P Chevrolet while awaiting a months-away second Intrepid.

Riley didn't fault Miller’s decision to forego the endurance races, which included Sebring.(interestingly, Road America’s long straights evidently later being “okay”).

"The Intrepid was designed for the short, bumpy tracks we had at that time," Riley said.

"Even though Daytona's got a reputation for a few bumps - something that is soon changing, I hear - back then it was still smoother than most other tracks we competed on. But the Intrepid just wasn't designed to go down long straights because there weren't many of those in the U.S., especially as compared to what they had in Europe.

"It wasn't designed to be an endurance car, either, so that meant races like Le Mans were out, too, and not only for the Mulsanne straight (Ligne Droite des Hunaudières)."

Producing downforce by the bushel, on long-enough straights the Intrepid and its 800-h.p. engine would meet an atmospheric wall so impossible to overcome that even sound barrier-breaker Chuck Yeager hisownself wouldn't have been able to push through it had he been at the car's controls.

Given sufficient straightaway length, the Intrepid's roughly 180 mph top-end speed was often 20 to 30 mph below that of competitors, which in top gear easily blew past, but which the Intrepid would soon handsomely reel in, braking deeply into following turns and easily throttling past as Riley's aerodynamic wizardry keep the car squarely on otherwise unseen railroad tracks.

With the longest races and straightaways all but completely ruled out and a time-shortened but successful Firebird International Raceway test completed, the Intrepid officially announced itself in the Mar. 3, 1991, Toyota Grand Prix of Palm Beach with an out-of-the-box, in-your-face debut.

The second venue of that year's IMSA 1991 GTP schedule brought the debut of the brand-new but relatively unknown Chevrolet Intrepid RM-1, which Taylor promptly qualified sixth then continued to surprise the paddock still further with a second-place race finish after going toe-to-toe with the day's goliaths: just behind Davy Jones' first-place TWR XJR-10 and ahead of a third-place and reigning GTP points champ Geoff Brabham's Nissan NPT-90.

"Of course, a win would've made it all that much better," Riley said, "But never underestimate the fun to be had in watching jaws drop, too."

Evidently, enough did.

"Before the race we'd gotten a lot of attention from fans when we rolled it off the truck," Riley said, "But car owners started queuing up after the West Palm race. Right away there was a lot of interest in that car."

Next: “All in All, We’re All Just Bolts in the Armco”

Later,

DC

No comments:

Post a Comment